Bottom line: Manufacturers who choose to incrementally add quality to their operations invite mediocrity, while those that choose to ingrain quality management at an enterprise level, deep into the DNA of their business models profitably excel.

Quality is the one attribute any manufacturer cannot hide – it screams who they are louder than any marketing campaign or PR strategy. Nothing says more about a manufacturer than how they prioritize quality management in manufacturing and information, intelligence, systems and processes necessary to excel in this critical area. In service industries, the higher the quality and more consistent a customers’ experience the higher the profitability of a business (Kimes, 2001). A study by Accenture and the National Small Business United Group (NSBU) showed that mid-tier manufacturers who attained the highest level of quality also were more profitable than their peer group companies (Quality, 1993).

Manufacturers who choose to embed quality deep into their enterprises, doing the hard work of making it a core part of their DNA over time see the following benefits:

- Reduced manufacturing costs attributable to less material waste;

- Greater efficiency of tools and manufacturing equipment;

- Greater optimization of skilled workers’ time and talents;

- Improved supplier quality;

- Improved traceability across the entire production process;

- Continual reductions in non-compliance.

Orchestrating all of these measurable gains together to create a unified enterprise quality strategy makes any manufacturer significantly more agile, enabling the ability to reconfigure operations, processes, and business relationships in real-time (Alexander, 2002).

Quality Management in Manufacturing: Strategies For Improving

This is the first post in a series that explains why manufacturers need to adopt a more enterprise-wide approach to quality, not allowing these systems to be siloed, delivering limited effectiveness as a result. The series will focus on how manufacturers can use the Six Sigma DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control) methodologies to get the most value from their quality management efforts. Three of the five elements of DMAIC are covered in this first post.

Complex manufacturers need to get beyond the myopic mindset that isolated, non-integrated quality management systems are good enough. That mindset invites mediocre performance when what’s needed is a strong focus on enterprise-wide results. Of the many strategies manufacturers are using for improving quality management performance, the following five are delivering solid, long-term results:

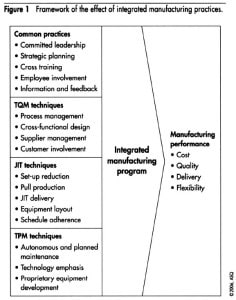

- Creating and reinforcing a strategic framework of quality that permeates every aspect of a manufacturer’s value chain is essential. Taking a piecemeal, incremental approach to quality management leads to information silos and fuels political infighting over quality performance, creating more problems than it solves (Gunasekaran, Goyal, Martikainen, Yli-Olli, 1998). A unified framework of quality management that integrates common practices, TQM, JIT and TPM techniques at a minimum is essential (Cua, McKone-Sweet, Schroeder, 2006). The graphic to the right shows how one suggested framework can be used for defining an integrated manufacturing program that leads to greater manufacturing performance.

- Supplier quality management objectives need to be defined before procurement and strategic sourcing is undertaken and integrated into inbound inspection, traceability and audits. Manufacturers who make the deliberate decision to invest in supplier quality management from procurement and strategic sourcing through fulfillment have greater control over cost of quality and greater visibility into overall manufacturing quality performance (Gunasekaran, Goyal, Martikainen, Yli-Olli, 1998). For complex manufacturers who have mixed-mode manufacturing strategies that have a multiplicative effect on supplier breadth and depth, ingraining supplier quality management is crucial to their success.

- Quality Control and compliance departments need to get beyond just reacting to quality management problems and take a much more proactive, strategic approach instead. Conrad Leiva’s great white paper Proactive Quality Management Requires Integrated Execution illustrates this point. He points out how siloed applications like FRACAS (Failure Reporting, Analysis and Corrective Action System) can make manufacturers more myopic and siloed in how they manage quality. He points out that too much focus on reactive processes including final product inspection, documenting problems and failures, and tracking failure and correction metrics can rob manufacturers of the benefits of a proactive approach to quality management. These include greater focus on process standardization, visual aids, process control, configuration verification, in-process inspection, Statistical Process Control (SP{C), and several others. You can find his entire white paper here> Proactive Quality Management Requires Integrated Execution.

- Measurements of quality performance are the baseline that supplier management, production, fulfillment and services measure themselves by. Manufacturers who improve the most on the most critical dimensions of quality are using metrics and key performance indicators (KPIs) to evaluate the entire value chain, not just selected functional areas (Gunasekaran, Goyal, Martikainen, Yli-Olli, 1998). The most valuable metrics according to studies conducted of quality metrics’ impact on profitability include defect rates, cost of rework, warranty expenses, after-sales service costs, opportunity costs and costs of good and bad quality (Gunasekaran, Goyal, Martikainen, Yli-Olli, 1998).

- Quality process control programs need to be based on metrics and KPIs that serve as guard rails to keep quality management on track to meeting and exceeding customer requirements first. Reducing product variability based on unique customer requirements using Six Sigma’s DMAIC methodology galvanized a manufacturer to what matter most, which is keeping existing customers purchasing products and attracting new ones through superior quality (West, 2003). Quality process controls need to be engrained into the overall DNA of a manufacturing company to strengthen and sustain business model agility in the face of economic uncertainty and turbulence (Gunasekaran, Goyal, Martikainen, Yli-Olli, 1998).

Sources:

Alexander, D. (2002). Improving manufacturing performance. Quality Congress. ASQ’s .Annual Quality Congress Proceedings, 725-732.

Chenhall, R. H. (1997). Reliance on manufacturing performance measures, total quality management and organizational performance. Management Accounting Research, 8(2), 187-206.

Cua, K. O., McKone-Sweet, K., & Schroeder, R. G. (2006). Improving performance through an integrated manufacturing program. The Quality Management Journal, 13(3), 45-60.

Gunasekaran, A., Goyal, S. K., Martikainen, T., & Yli-Olli, P. (1998). Total quality management: A new perspective for improving quality and productivity. The International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 15(8), 947-968.

Kimes, S. E. (2001). How product quality drives profitability. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 42(3), 25-28.

Murrin, T. J. (1982). One major company’s steps for improving quality and productivity. Quality Progress, 15(10), 14.

Quality affects profitability. (1993). Quality, 32(8), 7.

Rudy, M. J. (1992). Integrating information for manufacturing quality. Quality, 31(12), 14.

West, J. E. (2003). Strategies for improving business performance. Quality Progress, 36(10), 87-89.

Free iBase-t eBook: